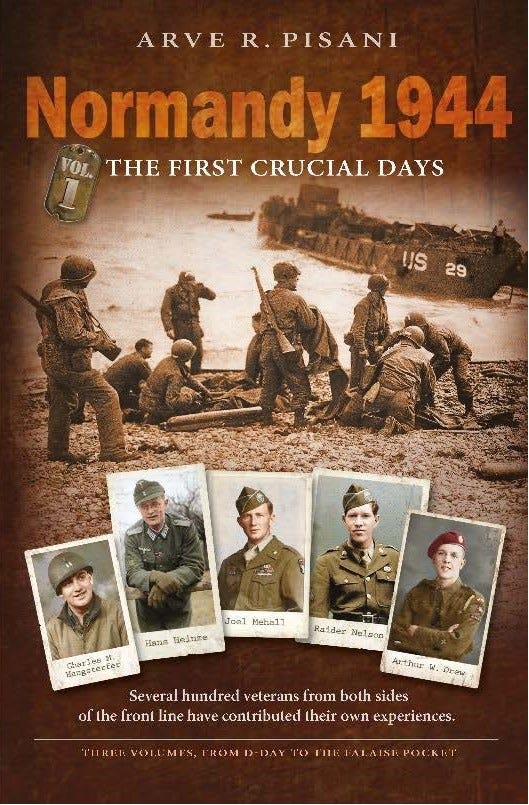

Omaha Beach, Early Morning June 6

In the bay off Omaha Beach, the ocean was ominously heavy. Waves came rolling in from the channel with violent force. Six thousand yards outside of the beach, 29 amphibious DD tanks[1] from the 741st Tank Battalion fought to stay upright in the rough seas. One-by-one the canvas screens that held them afloat ripped, and one-by-one the vehicles disappeared into the frothing, greedy sea. A total of 27 of them vanished forever. Some of their crew were unable to get out in time, and these men followed their steel caskets to the bottom of the Channel.

Battleships, cruisers, and destroyers opened fire at 5:50 a.m. The largest shells sounded like express trains as they tore through the morning air. The noise was deafening. Aboard the landing crafts leading the attack on Omaha Beach, the men stared tensely and nervously toward the shore, just as countless men were doing along other beaches. They faced a coastline more beaten and bruised by offshore bombardment than perhaps any single coastal strip had been before. Above their heads a steady stream of munitions passed on their way to impact among the smoking and burning foothills, as they had done for almost half an hour already. No living thing could survive such a bombardment, the thought of which provided invaluable moral support for the drenched, cold, and anxious men. One after the other, they noticed a new sound. A low, humming noise that kept growing in strength. Wet, pale faces turned to the sky and stared. At once, they were there—the planes. Bombers and fighters. They showed up in countless numbers, almost wingtip-to-wingtip.

***

“Bombers in the sky!” Sergeant Krone in WN 62 on the hill above Omaha Beach suddenly called out. The men listened intently. The sound of aircraft engines was getting louder by the moment, growing to a deafening roar. Then came the grim whistling from numerous bombs on their way down. The soldiers scrambled for cover. To their great surprise, only two of the bombs exploded in the strongpoint. The rest fell in the open area behind them. The airplane crews must have dropped the bombs too late out of concern for hitting their own men. This would have fatal consequences, as most of the defensive nests along the beach were left unscathed and the bomb craters that the soldiers would need for cover as they crossed the open sand were nowhere to be found. Unharmed but a little shaken nonetheless, Lieutenant Frerking called the gun emplacement in Houtteville. He feared the worst. But Sergeant Meyer answered and reported that no one had gotten so much as a scratch. The battery’s cannons were without damage.

A few hundred yards west of WN 62, 21-year-old Hans Heinze curled up in a trench. When approaching grenades exploded close by, he felt the earth strike violently against his chest. The air pressure swept over the trench, tearing leaves and branches from bushes and shrubs. Fortunately, he had come down from the lookout tree in time. The noise from exploding bombs and grenades was almost unbearable, but luckily most of the bombs fell further inland. Where he lay, he was anxious for his comrade, Lieutenant Feller, who was some distance away with 6th Company. Heinze could see violent explosions around 6th Company's position.

Carefully, he looked once more over the edge of the trench and out over the sea.

The invasion fleet had now grown into an armada of large and small ships and boats. Towards the horizon lay the great warships, while small landing crafts had set their course straight for him. From time to time, they disappeared almost completely into a valley of waves before they could be seen again coming steadfastly towards him.

Utah Beach, Early Morning June 6

Back at strongpoint WN 5 on the sands that would soon be known as Utah Beach, Lieutenant Arthur Jahnke got up in a hurry as the last bombers disappeared overhead. Smoke was drifting along the beach from several fires. The strongpoint looked like the face of the moon. Fortifications built within just the last few weeks had been completely bombed to pieces. The anti-tank cannon had been turned into scrap metal. An 88 mm had also been severely damaged. Two ammunition bunkers had been blown to bits and the machine gun positions buried in sand. The losses, however, were small. The men had stayed in their concrete bunkers that the bombers had failed to penetrate. The mess corporal, an older man from Ruhr, came running towards Jahnke, seemingly panic-stricken.

“Everything is ruined, Lieutenant!” he yelled. “The reserves are on fire! Everything is ruined!” His face was pale. With a stern expression, he added: “We must surrender, Lieutenant!” [2]

The 23-year-old lieutenant could feel panic lurking just below the surface. He knew the feeling from the Russian campaign. Jahnke barked at the older reservist and ordered all men to their posts. Then he hurried along to a rectangular building covered with a large camouflage net that housed, among other things, the telephone equipment. He called up WN 2 and spoke with Lieutenant Ritter. While they were talking, the calls came again:

“Enemy aircraft! Take cover!”

A new wave of planes approached from the ocean, this time very low. They turned instantly and aimed straight for WN5. Rockets left their wings and flew like arrows toward the strongpoint. The two corner bunkers were blown to bits; the rockets hit right in the embrasure of one of them. The stored 40 mm ammunition also blew up. Gruesome scenes played out. The men in the two bunkers were either killed or critically wounded. Calls for medics filled the entire strongpoint.

***

Bombardment group A, which would bomb the Utah sector, opened fire at 05:50 a.m., 40 minutes before H-hour.[3] For the men in the small attack vessels, it was as if the world had suddenly stopped breathing. The air was torn with brilliant muzzle flashes and the violent thundering of detonating munitions. Above their heads flew heavy 15-inch shells, ejected by HMS Erbus’ cannons. Together with the USS Nevada’s 14-inchers, they sounded like runaway express trains.

For the men in strongpoint WN5, it was as if the world had gone completely crazy. The large battleship and destroyer shells struck the sand dunes everywhere around them. Some impacted directly into the strongpoint, leaving only death and destruction. The stone house with the telephone switchboard, the officer accommodations, the mess hall, and the shower facilities collapsed. Trenches were buried. The fire-control post of the flame throwers received a direct hit. Minefields detonated. The shock waves knocked the wind out of the survivors as they desperately pressed their bodies to the ground. They prayed, cursed, and lay awestruck with fear.

Then sounded a cry through the air: “The ships!” Out in the ocean, countless bobbing rows of approaching landing crafts became visible. The hostile bows defiantly edged ahead through the waves. The ocean sprayed white sea foam all around them. Lieutenant Arthur Jahnke and his men in strongpoint WN 5 had only a few hours left before death or captivity would free them of the fear and suffering that was this war.

***

Sergeant Arthur B. Bertini followed one of the first landing crafts onto Utah Beach. He belonged to the 29th Field Artillery Battalion, which was directly supporting the 8th Infantry Regiment. The unit had been supplied with self-propelled 105 mm howitzers. The raging ocean had made the crossing from England very difficult, and they felt a sense of relief as they approached the beach. As they were passing the USS Nevada, she broadsided, and Sergeant Bertini could have sworn that the LST he was aboard jumped in the sea.

Five hundred yards out portside, and slightly ahead of them, another LST edged toward the smoky beach, its deck packed with men and vehicles. This was the B-battery in the same unit as Bertini. Suddenly, as the Sergeant looked over at the LST, a column of black smoke and a fierce flame shot through the air. They felt the air pressure as a huge roar filled their ears, drowning out all other sounds. The LST had hit a mine. In the intense flash, Bertini watched as the vessel, its deck now cleared of men, folded in on itself and rose again before disappearing into the depths. Later, they learned that only a small number from the B-battery had survived. Stunned by this terrible sight, they stood and watched the sea being whipped into foam around the B-battery’s final resting place. Men they had trained with and had come to love were now gone forever.

Somewhat farther out in the rough seas, the almost 30-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Edward A. Bailey,[4] commander of the 65th Field Artillery Battalion, was approaching the beach. Bailey was born on 13 June 1914 in Coshocton, Ohio. He had led the battalion into combat in Tunis and in Sicily. Now he was heading into his third campaign. Along with the commander of the 8th Infantry Regiment, Colonel James A. van Fleet, he observed the low-lying coastal strip in front of him. The small landing craft was being tossed around violently. The firings they had been exposed to indicated that the air force and fleet artillery had done their jobs. They encountered no enemy fire of significance, and the actual landing went off without a hitch, almost like one of their maneuvers down in Devon.

Now safely ashore, Bailey completed a visit to van Fleet’s command post before returning to the beach to await the transfer of his car. Lieutenant Colonel Bailey had left the disembarkation of the battalion to his second-in-command, Major Delbert L. Conkright, who had extensive experience handling heavy equipment on American oil fields.

The men from the 65th Field Artillery Battalion, veterans from both Tunis and Sicily, quietly started working on the beach. Everything was proceeding according to plan so far. There were no requests for artillery support from the forward observers who had moved in with the infantry.

All the 18 armored 105 mm self-propelled guns stood operational on the beach, just waiting. Bailey felt a little frustrated. With all the paratroopers inside the country and the 8th Infantry Regiment, who needed no support, he could not justify any firing orders. His mood soured further when one of the service battery trucks took a bullseye hit from German artillery just as it drove up from the sea. A car and observation plane the battalion had brought, both of which were dismantled and loaded onto the truck, went up in flames.

Bailey was determined to get the battalion off the beach before nightfall to contact the 101st Airborne Division, mostly because he expected the German air force to take special care of the beach area during the coming nights. Unfortunately, their progress was hindered by an inadequate provisional bridge the engineers had erected over a crater in the road. It was calculated to hold only about half the weight of the battalion’s heaviest vehicle.

Bailey knew who he could approach with this problem: Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt. The Brigadier General had received special approval to disembark together with the first assault troops from the 4th Infantry Division. He was an old friend of the 65th Field Artillery Battalion from Tunis and Sicily and had visited them several times in England. There, he had spoken of the old campaigns and speculated about the coming invasion. Often, he could be heard saying: “It will be a lot of fun.” And they knew he meant every word. Those who saw him this morning on Utah Beach noticed that he appeared to be having fun, indeed. Bailey presented him with the problem of the bridge and argued that American engineers habitually designed a considerable safety factor into the equipment. “Get to it,” was Roosevelt’s short answer from where he stood observing the traffic. The walking stick that was his weapon made an imperious movement.

Omaha Beach, Company F, H-hour 06:30[5]

Back on Omaha Beach, everything was changing. The beach soon would be known as Bloody Omaha to the world. The entire F Company of the 16th Infantry Regiment took part in the first attack wave.[6] This tradition-rich regiment had been the first American regiment inserted into the first World War. Now it was leading the charge on Fortress Europe, Hitler’s Atlantic Wall.

Company F was divided into six assault boats, with the staff troop in one and five other troops in their own boats respectively. After the men had boarded the assault boats, the vessels spread out as much as possible so they could attack the beach in a wide line. The company commander, Captain John G.W. Finke, was aboard the HQ section along with the deputy commander, Lieutenant Howard Fearre, Sergeant Thaddeus A. Lombarski, and 27 others. Captain Finke stood foremost in the boat. Under his steel helmet dripping with water from the sea spray, he stared towards shore. He could see that the coxswain was taking them too far left and instructed him to correct the course. But it was too late. The boat was brought ashore 200 yards left of its targeted landing area.

The time was approaching H-Hour, 6:30 a.m. The landing craft with the 1st section under the command of 24-year-old Lieutenant Aaron E. Dennstedt, from Los Angeles, California, approached the beach at full speed along with Staff Sergeant Andrew Nesevitch and the rest of the men. The beach and the hillside were slightly blurred behind a smokescreen. The fighting was increasing and they could hear projectiles hammering against the bow ramp. Grenades exploded around them and sent geysers of water high into the air. The Higgins boat[7] plunged its stubborn bow into every wave and sent the frothy, cold water into a spray, drenching the tightly packed soldiers. It was tremendously uncomfortable for them. The landing craft with its big 225-horse Grey diesel engine was charging full speed ahead at 10 knots. “It doesn’t feel particularly fast when the grenades are coming down so closely around the boat,” said a soldier from the 29th Division.

The boat carrying the 2nd section was also going at full speed toward Omaha Beach, loaded with soldiers whose faces were transfixed on land. Lieutenant Bernard J. Rush and Sergeant George B. Hammond stared with strained eyes toward the shore. The water ran off their steel helmets and clenched faces. The beach and the hillside behind it were difficult to see because of the haze and smoke. The lieutenant threw another glance over the ramp and shouted over to Hammond that it must be steered more to the right, but once again, the coxswain to the 2nd section was reluctant to change course until it was too late. They ended up 600 yards farther to the left than what had been planned.

Lieutenant Glendon S. Siefert, Sergeant Fary Williams, and their men in the 4th section had some trouble during the landing. A large LST was close to sinking them completely. They caught up with the other boats, but 100 yards from the shore the coxswain thought he was in the wrong place and turned around in the choppy sea. Full speed ahead brought them back out to sea about 300 yards before they could once again turn around and head for the beach.

Even the 5th section seemed to come in too far to the right. The section commander, Lieutenant Otto W. Clemens and the troop deputy commander was thrown off balance when a shell exploded to the right of their landing craft. The coxswain swung automatically to the left, but a second shell landed on the left side of the boat.

Lieutenant Clemens shouted, “Bring her in. Let’s get the hell out of this boat!”

The ominous sound of projectiles cut through all the other noise as German MG 34 machine guns opened fire and peppered the bow ramp. The boat stopped with a jerk, facing the beach. The hammering of bullets against the hull continued, but the ramp could not be opened. When they finally got the ramp down, the fire had ceased. Fortunately, the enemy was either out of ammunition or reloading.

The Higgins boat with 1st section and Lieutenant Aaron E. Dennstedt was almost at its destination when, barely fifty yards from the shore, it was thrown against one of the beach obstacles and nearly capsized. The Navy coxswain frantically struggled to free the boat, but without much success. The noise around them was deafening. Projectiles from machine guns made a frightening clatter of steel against steel. Men cried in despair that the ramp had to be lowered. Suddenly it slid down. The machine gun fire had ceased.

Lieutenant Dennstedt saw the ramp fall and ran out into the sea. The cold water reached the 24-year-old lieutenant to his neck. Behind him followed Staff Sergeant Andrew Nesevitch and the other soldiers. Many were shot dead before they even got off the ramp. Dennstedt could see the beach with a high tide mark of 75 yards in front of him as he struggled through the foaming sea. The high tide mark gave hope of some coverage where the sea had accumulated its sediment.

Mortar shells had started falling on the beach now. The blasts surrounded them with flashes of orange and a hail of steel fragments. Dennstedt reached the beach soaked and breathless. He turned around and yelled to the men behind him to advance. But in that same moment, he was hit by a hail of bullets from a machine gun and fell dead in the sand. Out of the section’s 31 men, only 14 managed to get onto the beach.[8]

Tragedies were unfolding quickly along all of Omaha Beach. The

whole company was subjected to the same brutal treatment. The men in Lieutenant Siefert’s 4th section struggled through waves that reached to their chests as the sea was whipped into foam by rifle and machine gun fire. Siefert was hit but managed to make his way to the beach, where he died a short time later.

Otto W. Clemens, who was leading the 5th section, was also battling through deep water coming ashore. The entire squad was under intense fire and many were wounded. The water turned red around them.

“Keep going! Keep going!” Lieutenant Clemens shouted as he reached the beach, waving the men forward. Then, with a sudden jerk and a thud, he fell to the ground and died.

The crossfire from the German defense was so intense that only seven men managed to reach the sediment. Others were left lying in the water; their bodies slowly washed ashore in the surge.

Medic Morris T. Levine was seriously wounded where he sat crouched and catching his breath, sheltered by the bank. Despairingly, he looked down toward the waterfront where several wounded comrades desperately tried to take shelter, either behind the beach obstacles or in the sea. With great pain and at the risk of his own life, he grabbed the first aid kit and ran to their rescue. Levine continued to give first aid until there was no one left to help.[9] The situation was critical for F Company. Only two officers remained able to lead their men.

[1] Duplex Drive (DD) tanks were specially built amphibious Sherman tanks sealed to be waterproof and equipped with floatation devices. They were able to maneuver in water using a propeller.

[2] Invasion – They’re Coming! av Paul Carell

[3] For Utah Beach and Omaha Beach, H-Hour was 6:30 a.m. For Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches, H-Hour was 7:30 a.m.

[4] Edward A. Bailey, letter to author

[5] 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Division

[6] Combat Interview: 1st Infantry Division, Omaha Beach June 6, 1944.

[7] Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP)

[8] Combat Interview Company F, 16th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division, Omaha Beach June 6 1944

[9] Morris T. Levine was awarded the Silver Star for this effort.